Social engineering, especially phishing in all its forms (emails, text messages, phone calls, QR codes, etc.), remains one of the main attack vectors.

In many attack scenarios, social engineering is a preferred lever for gaining initial access: moving from the position of an external attacker to that of an attacker with a foothold within an organisation’s IT system.

As a result, social engineering and phishing are naturally used in red teaming exercises.

In this article, we explore the link between social engineering and Red Teaming. After clarifying the respective objectives of a social engineering audit and a Red Team exercise, we provide an overview of the main threats targeting the human factor. These issues are then illustrated by realistic scenarios, before addressing the levers that can be used to protect against them.

Comprehensive Guide to Social Engineering and Red Teaming

- Social engineering Audit and Red Teaming: Objectives, Differences and Complementarities

- Social Engineering and Threat Intelligence: Overview of Threats Targeting the Human Factor

- Phishing and Red Teaming: Illustration of a Realistic Attack Scenario

- How to Prevent Social Engineering Risks?

Social engineering Audit and Red Teaming: Objectives, Differences and Complementarities

While social engineering is frequently used in red teaming exercises, the approach taken in a social engineering audit is different.

A Red Teaming exercise aims to assess an organisation’s overall security level by simulating realistic and sophisticated attacks based on the TTPs (Tactics, Techniques and Procedures) of real attackers. Social engineering is one of several tools used in this exercise.

Conversely, the main objective of a social engineering audit is to raise employee awareness of threats targeting the human factor. It is generally based on phishing simulations designed to measure users’ ability to detect and respond to attempts at manipulation.

In a Red Team context, social engineering can be exploited at all stages of the attack chain. It is not limited to gaining initial access, but can also facilitate lateral movement or privilege escalation. For example, a phishing campaign conducted from an already compromised email account can significantly increase the chances of success.

In comparison, in the context of a social engineering audit, gaining initial access is often the end goal. An anonymised screenshot of a compromised account during a phishing simulation is an effective way to illustrate the risks and raise awareness. In practice, most audits stop at this stage.

That said, whether it is a dedicated audit or a red teaming exercise, any social engineering simulation must be realistic and contextualised. While threat intelligence is essential for a Red Team, adapting scenarios to current threats is just as important for conducting effective awareness campaigns. Furthermore, these campaigns cannot be limited to email phishing and must incorporate all emerging techniques.

Social Engineering and Threat Intelligence: Overview of Threats Targeting the Human Factor

Initial access: phishing and compromised credentials

As mentioned in the introduction, social engineering, and phishing in particular, remains one of the main vectors for initial access. Another equally formidable lever is the use of compromised credentials.

In the cybercriminal ecosystem, certain groups specialise in selling initial access, commonly known as Initial Access Brokers. These actors monetise access to compromised information systems, facilitating the work of other malicious groups.

More broadly, the Cybercrime-as-a-Service model, including Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) and Phishing-as-a-Service (PhaaS), contributes to the democratisation of cyberattacks. Now, even inexperienced attackers can carry out sophisticated attacks and bypass advanced technical protections.

AiTM phishing: bypassing two-factor authentication

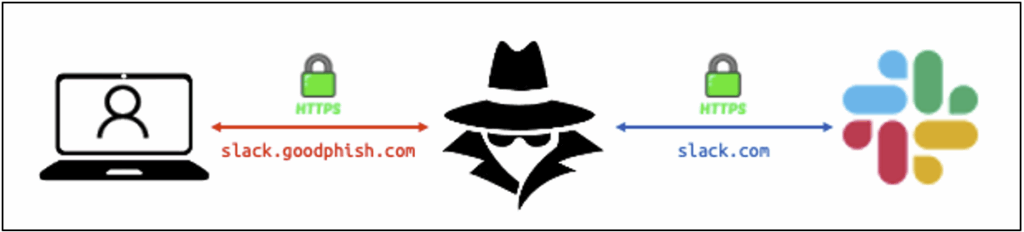

Some phishing kits, available on the dark web or via platforms such as Telegram, can bypass most two-factor authentication mechanisms. They rely on the AiTM (Adversary-in-the-Middle) phishing technique, also known as MiTM phishing or reverse proxy phishing.

In this scenario, the attacker positions themselves as an intermediary between the victim and a legitimate service in order to capture authentication traffic.

This technique can be used to steal session tokens, which is often more effective than simply compromising credentials.

AiTM phishing can therefore compromise user accounts even when 2FA is in place. It should be noted, however, that some strong authentication methods, such as passkeys, remain resistant to this type of attack.

Targeting SaaS platforms and identity providers

Since 2023, numerous attacks using AiTM phishing have been attributed to groups such as Scattered Spider, targeting SaaS platforms and identity providers such as Okta.

SaaS applications are prime targets because they host potentially critical information (sensitive data, secrets, passwords). Compromising an instant messaging application, such as Slack, also makes it possible to launch particularly credible internal phishing campaigns from legitimate accounts.

Single sign-on (SSO) solutions are also prime targets. Compromising a single SSO account can provide access to all associated applications.

LOTS: diverting legitimate services

Another notable trend involves the abuse of features offered by legitimate platforms to host or distribute malicious content, an approach known as LOTS (Living Off Trusted Sites).

Attackers exploit services such as Google Docs to send notifications or share files containing phishing links. This method greatly improves email deliverability, as a message from a trusted service is more likely to reach the inbox than an email sent from a recently registered domain or one with a dubious reputation.

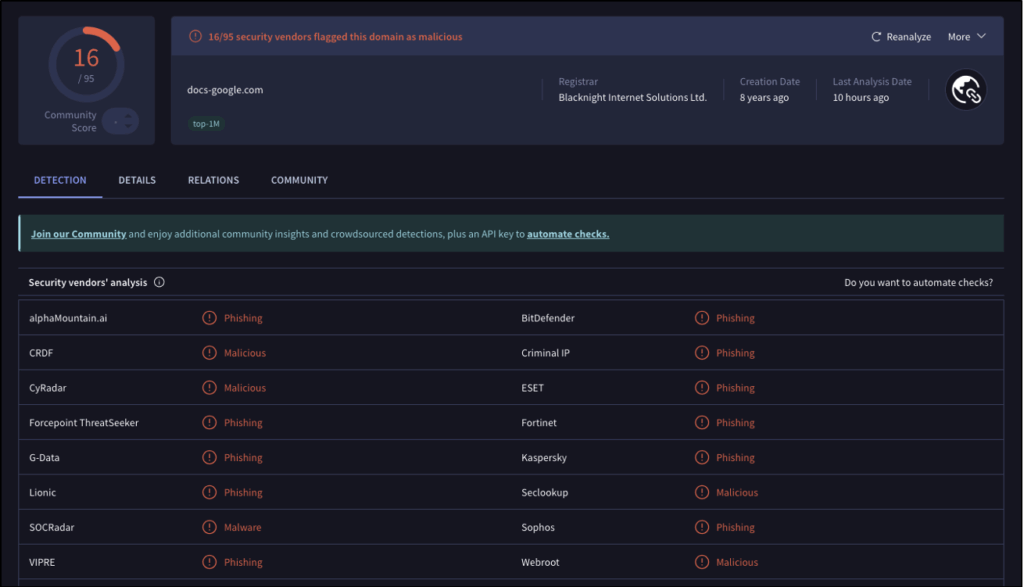

In fact, if the attacker registers and uses a domain name similar to google.com, certain technical protections will likely detect suspicious activity originating from that domain, for example:

Bypassing protections and new attack techniques

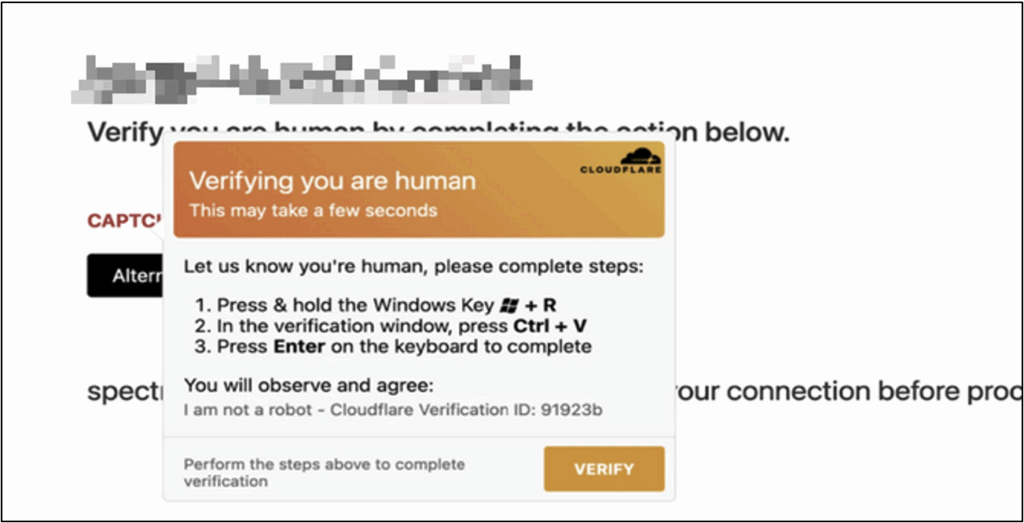

Attackers also use legitimate third-party services to host or protect their phishing sites. Integrating mechanisms such as CAPTCHAs allows them to bypass automatic analysis tools.

Attacks such as ClickFix, which have become widespread recently, exploit this sense of trust by offering fake CAPTCHAs that prompt victims to execute malicious commands on their own machines.

Voice phishing and hybrid attacks

With the improvement of anti-phishing protections for email, attackers are increasingly turning to other communication channels. Vishing (voice phishing) attacks have risen sharply in recent years.

A common scenario involves posing as an IT support member in order to obtain login details or authentication codes. Conversely, some attackers contact the help desk directly to request a password reset.

Hybrid scenarios combining several channels are also developing, such as callback phishing, where the victim is encouraged to call a phone number provided in an email.

The use of QR codes to hide malicious links is also part of the arsenal of modern attackers.

Summary of current trends

The main trends observed in social engineering include:

- trafficking in compromised credentials to gain initial access;

- the use of AiTM phishing to bypass two-factor authentication;

- increased targeting of SaaS platforms and identity providers;

- abuse of legitimate services to spread attacks (LOTS);

- an increase in vishing and multi-channel attacks.

In general, attack tools and techniques are becoming more widely available, enabling even inexperienced attackers to carry out sophisticated attacks. Advances in artificial intelligence are further accentuating this trend, particularly in Business Email Compromise (BEC) scenarios, where credible conversations can be generated quickly, in any language.

Phishing and Red Teaming: Illustration of a Realistic Attack Scenario

Like any security audit, a Red Team exercise begins with a target reconnaissance phase, prior to any intrusion attempts. Combined with information from Threat Intelligence, the data collected during this phase is used to design relevant attack scenarios that accurately replicate the TTPs of real attackers.

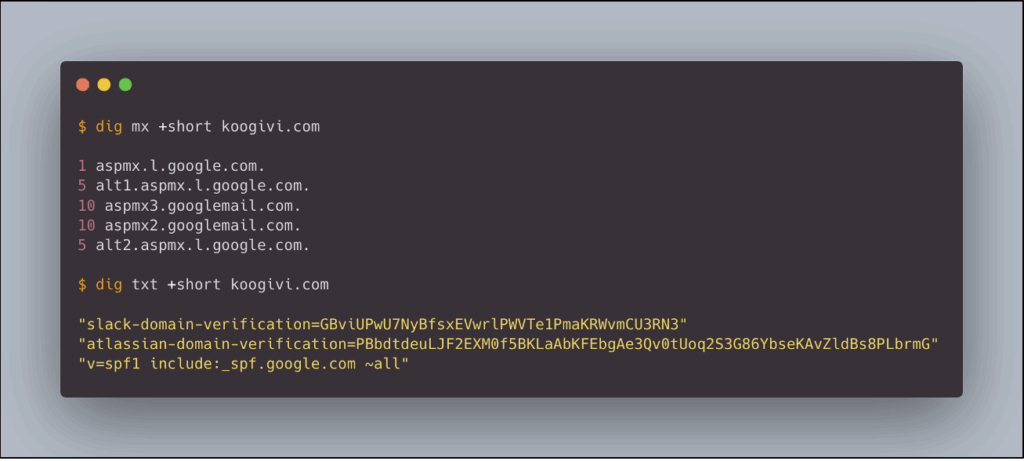

Analysing the technical attack surface is a key step in this reconnaissance. Studying the DNS records of domains belonging to the organisation provides valuable information. MX records identify the email provider used, while certain TXT records, particularly those used to verify domain ownership, can reveal the SaaS platforms used by employees.

For example, let’s assume that our fictional target, KooGivi, uses Gmail as its email service, as well as Slack and Atlassian.

Let’s also assume that authentication to these services is centralised via Okta SSO.

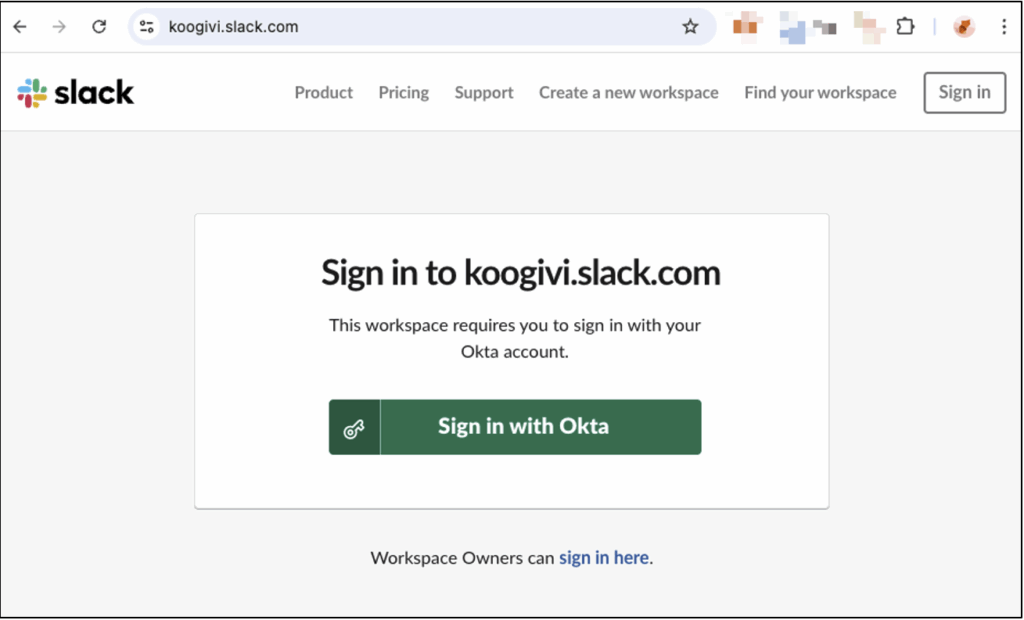

In this context, a relevant phishing scenario would involve sharing a file containing a phishing link to a fake Slack login portal from a Google account impersonating the CEO of KooGivi. The aim would then be to compromise Slack credentials and, ultimately, the company’s SSO environment.

Attack scenario sequence of events

The following demonstration video illustrates this attack:

Let’s take a closer look:

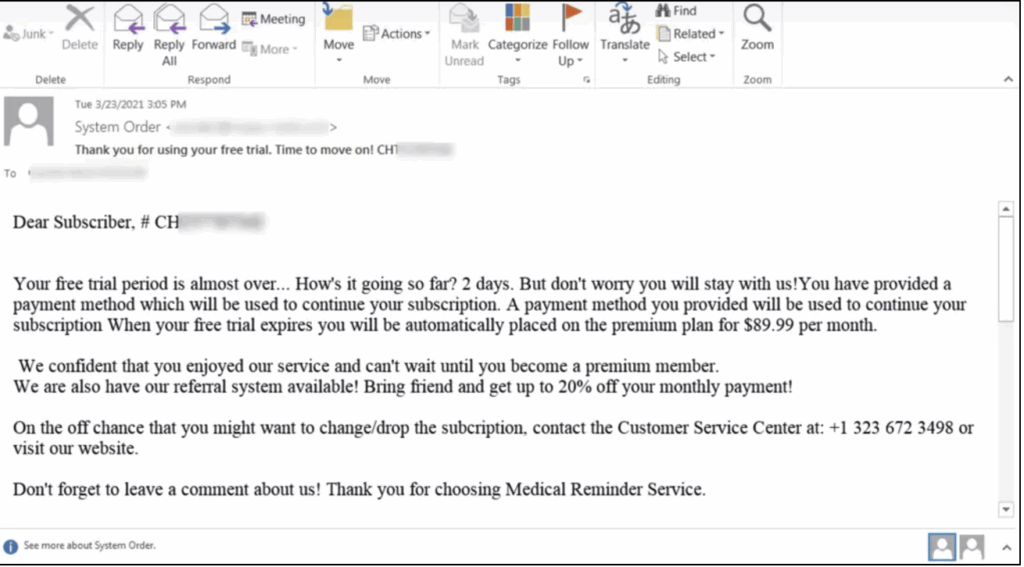

- The attacker creates a fake Google account impersonating Zaïa Jefferson, CEO of KooGivi (information found on LinkedIn). They then share a Google Form pretending to be an urgent update related to SSO authentication on Slack. The sharing notification is received directly in the victim’s inbox, rather than in their spam folder, because it is sent from Google’s legitimate infrastructure. At this stage, however, there are several clues that can help detect the attack:

- the sender’s email address is clearly visible in the notification;

- Google indicates that the sender is not part of the same Google Workspace organisation.

- Ignoring these warning signs, the victim opens the form and clicks on the link leading to a fake Slack login portal hosted on the goodphish[.]com domain. The phishing site uses an AiTM phishing technique, which proxifies traffic to legitimate services. The authentication page is visually identical to the official Slack portal, except for the domain name in the URL.

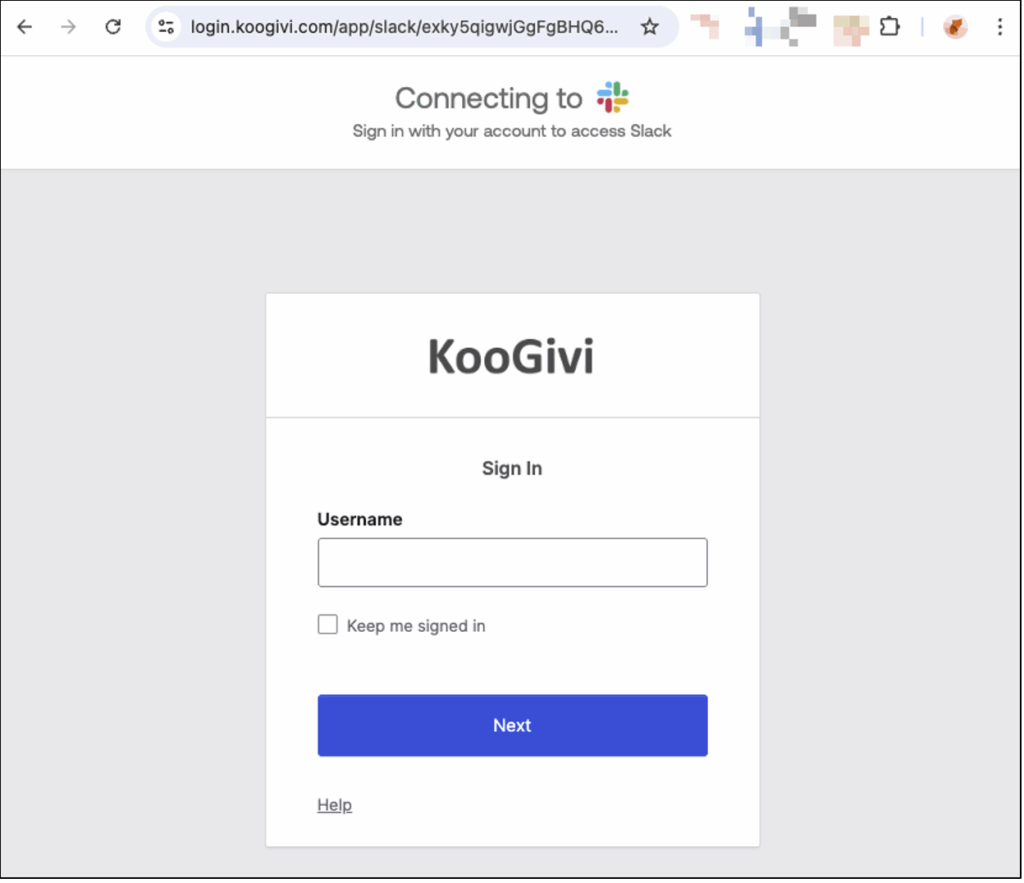

- NB: When attempting to log in to Okta SSO, an important clue could have alerted the victim: the absence of any login suggestions from their password manager.

- Once authentication is complete, the victim accesses their Slack account as normal, but this connection still passes through the attacker’s reverse proxy. At this point, the attack is considered successful: the Slack and Okta session tokens have been captured.

- The attacker then imports the captured sessions to directly access the victim’s Slack and Okta accounts without having to re-authenticate.

- Once logged into Okta, the attacker can access other applications integrated with SSO, such as Confluence, which is part of the Atlassian suite identified during the reconnaissance phase.

Why this scenario is realistic

This type of attack perfectly illustrates how social engineering techniques, combined with a good knowledge of the attack surface and advanced tools such as AiTM phishing, can bypass even robust technical protections.

It also highlights the importance of the human factor, both as a vector for attack and as the first line of detection.

How to Prevent Social Engineering Risks?

Reducing the risk associated with social engineering attacks, particularly phishing campaigns, requires a combination of technical measures and good user practices.

The key point to remember is that technical controls exist and must be implemented in order to:

- Limit employees’ exposure to social engineering attacks, for example by blocking phishing emails as early as possible using robust anti-spam policies;

- Facilitate the early detection of social engineering attempts that have not been stopped upstream, based on the principle that no technical protection is foolproof. This involves both theoretical awareness-raising activities and practical exercises, such as attack simulations, to test employees’ level of vigilance before real attackers do so;

- Enabling technical teams, particularly system and network administrators, to quickly identify any suspicious activity, such as a connection from an unusual location, again on the basis that no user is infallible.

That said, employee awareness remains a key factor: it is often the first, and indeed the main, line of defence against social engineering attacks.

Raise employee awareness of social engineering risks

When faced with social engineering attacks, a certain level of vigilance is essential. Trust does not exclude control, provided that a pragmatic and measured approach is maintained.

Identify sensitive, urgent or unsolicited requests

Any sensitive request, whether made by email, text message, phone or even in person (e.g. a supposed technician coming to inspect the premises), must be carefully verified. Such a request is not necessarily malicious, but caution is still advised.

In most social engineering attacks, the attacker seeks to get their target to perform a sensitive action (download a booby-trapped file, click on a malicious link or grant access to restricted areas) as quickly as possible. The urgency is deliberately emphasised in order to bypass the mechanisms of reflection and verification. Conversely, it is essential to take a step back, even if this can be difficult in certain contexts, and to rely on predefined verification procedures.

Unsolicited requests should also be a warning sign. For example, in an ‘MFA fatigue’ attack, an attacker who has obtained a user’s password sends multiple validation notifications until one of them is accepted, giving them access to the account. Similarly, pop-ups displayed in a browser should never be validated automatically, as they can also be a vector for attack.

Detecting the signs of identity theft

Identity theft: a key lever in social engineering

In most social engineering attacks, attackers impersonate trusted third parties, whether individuals or brands, in order to convince their victims to perform sensitive actions that jeopardise the security of their organisation.

A prime example is Business Email Compromise (BEC) attacks, such as CEO fraud. In this scenario, the attacker pretends to be a senior manager and requests an urgent transfer of funds. Psychologically, this urgency reinforces the authority bias, prompting the victim to comply with the request simply because it appears to come from a superior.

Domain impersonation vs domain spoofing

These identity theft attempts often rely on the use of domain names that are similar to legitimate domains, without being identical. Due to technical constraints related to email authentication (SPF, DKIM, DMARC), attackers generally prefer domain impersonation rather than direct spoofing.

For example, the phishing domain docs-google[.]com imitates the legitimate domain google.com, and more specifically the subdomain docs.google.com. The difference may seem subtle, but it is significant: docs-google[.]com is a separate domain, while docs.google.com is an official subdomain of Google.

Conversely, an email sent from an @google.com address by an attacker would constitute domain spoofing. Technically, this email would not be authenticated and would most likely be blocked or classified as malicious by email protections.

Limitations of conventional detection indicators

The domain name of each email address, link or URL must be carefully checked, whether in a message or in the browser’s address bar. However, as mentioned above, attackers are increasingly exploiting legitimate features of trusted services to distribute malicious content.

The advantage in terms of deliverability is considerable: using a reputable sending infrastructure maximises the chances of a message reaching the inbox rather than the spam folder. As a result, some classic indicators of phishing, such as a crude imitation of the sender’s domain, may be absent or much more difficult to identify.

Furthermore, brand imitation is not systematic. Attackers may also use generic but credible domains, such as loginprotect[.]net, consistent with the pretext used (‘suspicious activity detected’, ‘action required’, etc.). Similarly, the use of a personal address (e.g. @gmail.com) in a professional context should be a red flag.

Best practices for verification and internal coordination

When faced with this type of threat, an essential reflex is to verify any sensitive request via a secondary communication channel: phone call, instant message or face-to-face conversation. Failing that, it is recommended to involve a competent trusted third party, such as the IT department or management, using predefined communication channels.

In the event of a suspected or confirmed attack, internal communication and coordination are crucial. A rapid and collective response can often significantly limit the impact of a social engineering attack.

Special case of vishing: verify the caller’s identity

In the context of vishing attacks, it is essential to have robust procedures in place to verify the identity of callers. These checks should not rely solely on personal information such as name, date of birth, telephone number or email address, as this data is often easily accessible to attackers.

Even more sensitive information, such as an employee or social security number, can be obtained by a determined attacker, for example by spoofing IT support. This is why it makes sense to use pre-established trusted communication channels: call back to a known number, confirmation via internal messaging (Slack, Teams), or validation by an authorised third party.

Detect, alert and respond in the event of an attack or incident

Social engineering relies on exploiting psychological mechanisms to persuade someone to perform a risky action. Since every employee reacts differently to this type of manipulation, it is statistically likely that only certain people will detect that an attempt is underway, particularly when an attack targets several individuals.

In this context, one of the most effective responses is to quickly alert colleagues if there is any doubt. This can be done through a dedicated communication channel (such as Slack) to centralise information and prevent it from being lost. It is also essential that all employees remain alert to these reports, particularly those who are more exposed, such as new arrivals, employees returning from leave, or external contractors, who are often more isolated.

Direct reporting of suspicious emails from the messaging system should also be encouraged and made as simple and effective as possible from the user’s point of view.

Finally, knowing how to detect an attack is essential, but it is just as important to respond appropriately in the event of a compromise, without panicking. If, for example, an employee has entered their credentials on a phishing page, it is crucial to immediately alert the IT department and change their credentials to prevent the attack from escalating. Where possible, all of the user’s active sessions should be revoked. Application tokens (API keys, OAuth tokens, etc.) should also be checked and, if necessary, revoked, as they can be exploited by attackers as a persistence mechanism.

Reduce the risks associated with password reuse

It is common to reuse the same password across multiple services. However, this practice exposes you to a major risk: credential stuffing attacks. When an attacker obtains the credentials for one account, they can attempt to reuse them automatically on other platforms. Without two-factor authentication, this technique allows them to instantly access multiple accounts.

The best practice is to use a unique password for each service. While this recommendation may seem restrictive, particularly in terms of memorisation, it becomes realistic with the use of a password manager. This allows you to generate and store strong passwords (long, random and unique) without having to remember them.

Beyond password management, these tools also offer a means of detecting phishing attempts. Saved credentials are only suggested when the user is on the legitimate site, which can be a warning sign in the event of domain name imitation.

Finally, the use of a password manager must be regulated at the company level. Allowing each employee to choose their own tool can lead to visibility and control issues for IT teams, encouraging shadow IT and, as a result, increasing the overall level of risk.

Implement technical measures to prevent social engineering attacks and improve their detection

From a technical standpoint, companies have several tools at their disposal to reduce the impact of social engineering attacks. These measures are designed to:

- Filter attacks as early as possible in order to limit employee exposure;

- Facilitate the detection of attempts that manage to bypass these protections by helping users identify them.

Strong authentication

Even though traditional two-factor authentication does not provide complete protection against certain advanced phishing techniques, it remains an essential defence against credential trafficking. Whether compromised as a result of a phishing attack, a data leak at a third party, or the action of exfiltration malware (infostealer), credentials alone are no longer sufficient to access an account when two-factor authentication is in place.

In this context, attackers are forced to use additional techniques to bypass protection, such as MFA fatigue, AiTM phishing or vishing, which significantly increases the complexity and cost of the attack.

That said, some newer authentication methods, such as passkeys, offer increased resistance to phishing, even in its most advanced forms. These mechanisms, which are gradually replacing passwords, are now supported by a growing number of platforms, including Google and Microsoft. It is therefore recommended that they be considered for deployment in sensitive applications and accounts, either as a complement to or even a replacement for traditional two-factor authentication.

Email security: SPF, DKIM and DMARC

SPF, DKIM and DMARC are three email authentication standards that must be implemented in order to protect a domain name against spoofing attempts. They prevent attackers from sending phishing emails using an address belonging to your domain without authorisation, i.e. without having legitimate control over that address.

SPF

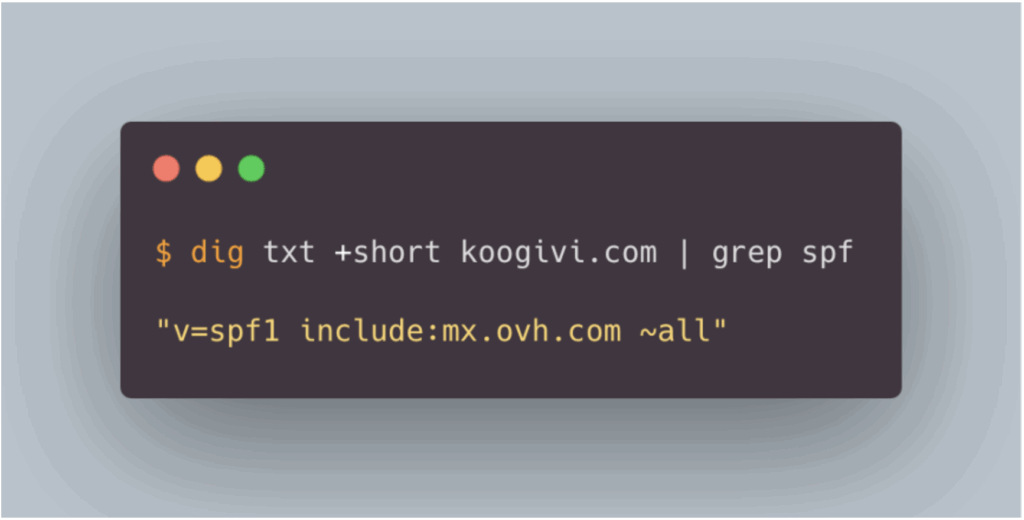

SPF (Sender Policy Framework) allows you to define which mail servers are authorised to send emails on behalf of a given domain. In practical terms, if an attacker attempts to send a message using the address support[@]koogivi.com from a server not declared in the SPF policy for the koogivi.com domain, the email will fail SPF authentication.

This mechanism significantly reduces the chances of the message reaching the recipient’s inbox.

The SPF policy is implemented via a DNS record, for example:

DKIM

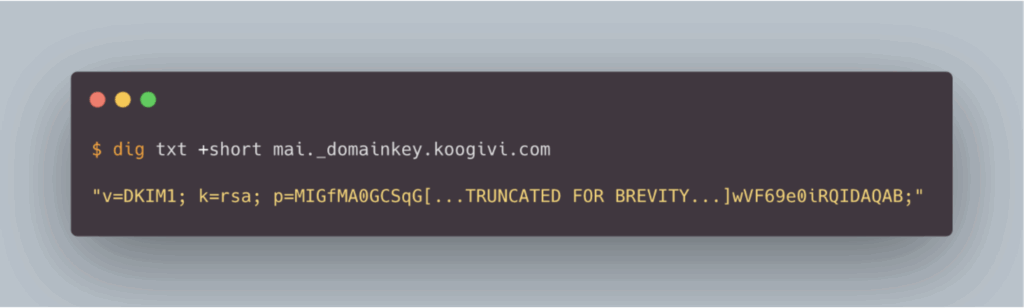

DKIM (DomainKeys Identified Mail) is an email authentication mechanism based on asymmetric cryptography. It verifies that the message was sent by an authorised server and that it has not been modified in transit.

In practical terms, if an attacker attempts to send an email using the address support[@]koogivi.com, the DKIM signature of the message, if present, cannot be validated, as the attacker does not have the private key associated with the koogivi.com domain.

Like SPF, a failed DKIM authentication significantly reduces the chances of the email reaching the recipient’s inbox.

The DKIM public key is published in a DNS TXT record, for example:

DMARC

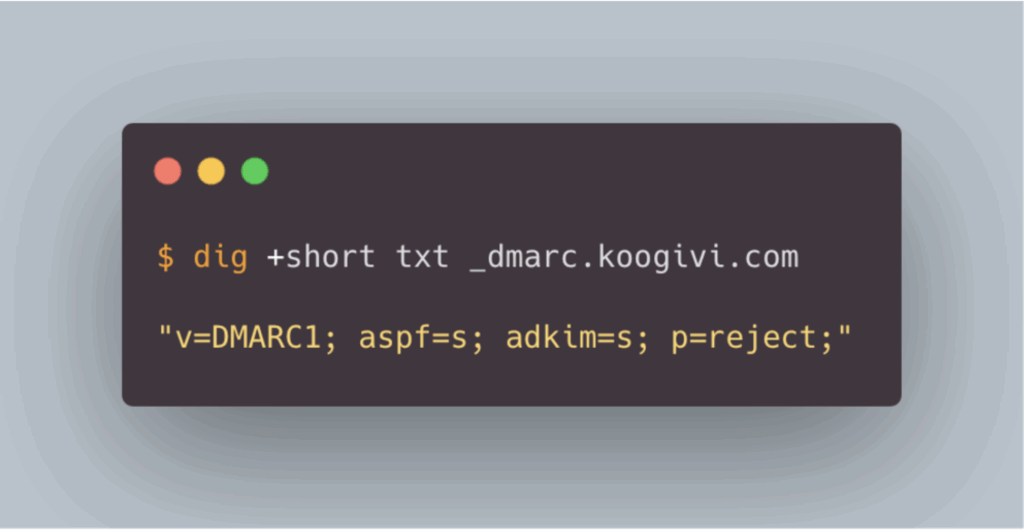

DMARC (Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance) allows you to define an explicit policy to be applied when SPF and DKIM checks fail. In addition to these mechanisms, DMARC introduces the concept of domain alignment, an essential element in effectively protecting against email spoofing attempts.

Without going into all the technical details, three distinct domains are involved in email authentication:

- the sending domain, corresponding to the sender’s address domain, visible to the recipient;

- the envelope domain, used for SPF verification and associated with the return address;

- and the signing domain, used when DKIM signing the message.

Without verifying the alignment between these domains, an attacker could visually spoof a legitimate address (e.g. support[@]koogivi.com) while using different envelope and signature domains under their control. They could thus validate SPF and DKIM checks using their own infrastructure, without being authorised to use the spoofed domain.

DMARC prevents this scenario by verifying that the domains used for SPF and DKIM are correctly aligned with the sending domain.

The DMARC policy is defined via a DNS TXT record, which allows you to specify the behaviour to adopt in the event of failure (quarantine or rejection).

In the example of an email using goodphish.com as the envelope and signature domain, but koogivi.com as the sending domain in order to impersonate a KooGivi employee, the email would not pass the alignment checks imposed by DMARC. With a strict policy (aspf=s and adkim=s) and a p=reject mode, the message would theoretically be blocked before it is even delivered.

Enhancing mailbox security

Technical protections can be put in place at the level of employees’ email accounts to filter out phishing attacks, particularly through anti-spam and anti-phishing policies. However, the features available, and their level of granularity, depend heavily on the email provider used.

For example, Gmail and Outlook, the two services we encounter most frequently during our audits, offer advanced protection mechanisms, including detection of identity theft or impersonation attempts, as well as automatic analysis of links and attachments.

In order to effectively protect employees from phishing attempts, it is therefore recommended that you familiarise yourself with and configure the security mechanisms offered by your email provider.

The following resources are a good place to start:

- for Gmail: documentation on anti-phishing and anti-spam protection

- for Outlook: overview of the protection features of Exchange Online Protection and Microsoft Defender.

Monitoring, security alerts, and risk-based authentication

Like the security mechanisms implemented in messaging services, many platforms, particularly identity providers, offer monitoring and administrator alert features in the event of suspicious activity, such as when logging in from an unusual location.

Solutions such as Okta offer advanced mechanisms for defining conditional access policies based on various contextual factors associated with a login attempt, such as the device used, the IP address or the geographical location. Each login is assigned a risk level, based on which appropriate security measures can be applied, such as requiring an additional authentication factor to complete access.

Equivalent features also exist for protecting Microsoft 365 accounts, via conditional access policies, and for Google Workspace, with similar control and alert mechanisms.

It is therefore strongly recommended that you familiarise yourself with the monitoring, alerting and conditional access control capabilities of the applications you use, especially those considered sensitive.

For example, the following resources are good starting points:

- documentation on security and alerts in Google Workspace

- overview of conditional access policies for Microsoft Entra/Office 365

- documentation on Okta’s risk scoring and adaptive policies.

Author: Benjamin BOUILHAC – Pentester @Vaadata